Darja Popolitova is an artist, teacher and doctorate at the Estonian Academy of Arts.

Editor: Keiu Krikmann.

This story is being told on behalf of the archetypal work of art of the artist, collector, and treasurer of Sillamäe Museum, Aleksandr Popolitov.

MORE UNSERIOUS

Psst! I’m right here! Yes, I finally decided to speak. I have been absorbing looks and touches for so long that I have become overwhelmed — and I want to pour out my soul, draw you into the vacuum of my attention, but this time through words.

Sometimes words tend to be perceived more clearly than visual metaphors. However, this does not mean that the latter does not have its particular innerworkings1. As an art piece, a visual metaphor, I have experienced many transformations hidden from the viewers’ perception. I got to know the world through experience — I was the source material, subjected to an artist’s countlesstouches and then to the gaze of the visitors of the exhibitions. Passing through these levels was fun and touching (also in the literal sense of the word). I want to talk about this haptic-visual journey, because my unique core, is hidden at the heart of these sensations.

All these years I have been exhibited in north-eastern Estonia, in exhibition halls,taking occasional trips tomuseums and galleries in Tallinn, Kärdla and Finland. Chewing on the pulp of the hall lights, I digested it in the sauce of the visitors’ gaze and sometimes even their touch. However, these encounters were timid, because of my status as anart object, which imposes certain “tactiloclasms”2 on the behaviour of people in such spaces.When looking atme, some whispered about the texture of my surface or my natural origin. No wonder — the exhibition labels detailing my existencestated: “Hymn to a Blossoming Stump”, “The Secret of the Black Grotto”, “Mountain Flowers in the Moonlight”, “The Birth of Agate”.

I witnessed the flourishing, albeit hard-

earned cultural life of Sillamäe3. I saw how the peculiar identity of the artists living this secret Soviet city with its picturesque granite-bouldery sea coast and pine trees developed. Now the city as acquiredan atmosphere of bittersweet nostalgia for a long gone era and its ceremonial neoclassicism.

When I say the cultural life was flourshing, I mean that almost in the literal sense of the word. I was annually shown at April exhibitions. The participating artists, the so-called Aprilists crystallised their artistic fantasies at a common exhibition groundall at once and in everything — like nature in spring4. Applied and visual artists as well as photographers awakened life with these exhibitions, which took place, of course, on April 1st, that is, on April Fools’ Day. This was to challenge ideas like fitness, coherence and seriousness of life, while giving a voice to diversity, quirkiness and disorder or, as it is said in a brochure from 2003, to “raw creative ideas, poetry, nature and impromptu actions”5, and in a brochure from 2017 — “[o]oh, how not to lose your face and issuean exhibition of a more unserious kind!”6.

At such events, there was poetry (“stupid”, of course) 7, dress-ups8, undressings9 and even removal of some parts of the body10. All of these theatrical performances took place among works of art — oil paintings, graphics and applied art objects. Such performances seemed to bring great pleasure to the public. Some people needed them like being wrapped in a thin and tight blanket on a cold night. I saw how some wroteoverly dramatic phrases in the guest book: “We have no reason to live without your art!”11 or “You have golden hands!”12, “I liked everything very much”13. There were also constructive comments such as à la “I am amazed and delighted by the 2003 April exhibition. I especially liked the wooden bouquet by A. Popolitov. <…> One can feel the great skill of [this] artist”14. No less emotional are the following: “All the pictures are very beautiful and being very origenally [sic] fantasised!!!”15 or “It was cool. Dope! Off the hook!”16

PORCUPINE’SQUILL

Just as with fish behind the aquarium glass, the visitors were knocking on me, while trying to hear my inner voice. But can they understand my intricate choreography of gestures? Can they untie the knot of my eternal haptic storyline?

It is clear that they can not. For them, I am a complete subject, a composition of materials. The image cannot reproduce the experience that happened inmaterial in its pure form, and especially post factum.

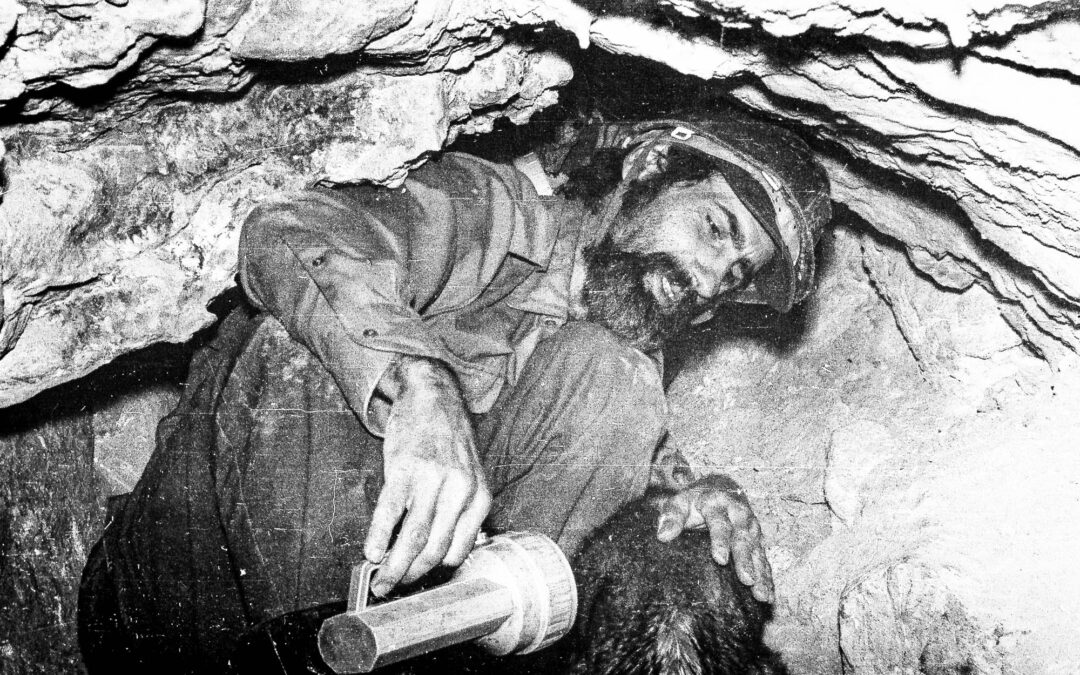

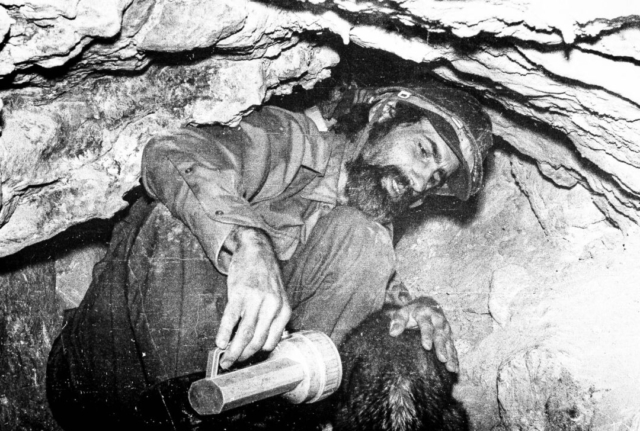

I know that there is wood, amethyst and onyx in me. But these are not just materials. These are the embodiments of an experience — experience of the body. Have you ever had to go down 140 meters into a cave or spend the night on the side of a high mountain? Feel a backpack with a metal frame clinging to youlike a stone? Move up the ascent, climb hour after hour? Then, with overwhelming pleasure, toss the backpack on the ground and set up camp?

Indeed, I have seen such pilgrimages more than once. I felt how the throat of the one who created me was dry somewhere in the Issyk-Kul region. The top of a mountain seemed so close, at spitting distance. But the saliva had ran out, as he “viciously climbed and climbed, however, the top still did not come nearer”17.

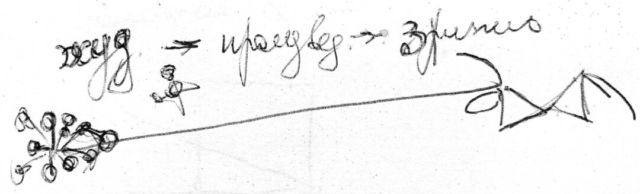

Where did he climb? What kind of diagonal, straight, and wavy lines did he need to weave into the myth of his life? I found the answer once — when I peeked into his notebook and saw ascheme illustrating the following: “artist → work of art → viewer”18. In it, it seemed to me, the semantic pattern of this mountain hike was expressed — if I am a work of art, then, according to this scheme, the artist was my creator, the same person who heard the hissing of the copperhead snake and felt the settling steam from the Tears of Bars waterfall19 on his beard…

In the flesh of this threefold relationship, I recognised the experienceofa mediated and unmediated kind. As there is, for example, malachite and there is pseudomalachite — both are called malachite, only pseudomalachite is much less common and differs from malachite in a specific bluish tint.

The scheme “artist → work of art → viewer” sets the theory of a rare (unmediated) experience. The experience of perceiving the spectacularity of nature — the theory of fascination. To perceive, to be embraced by the “given ‘sets’”20 of the atmosphere, the horizon, the light, the air, theparticular moment in time, “to see, standing forth from a cluster of data, an immanent significance”21 means to be impressed by an uncommon pseudomalachite.

And when that happens, for the artistit means to expose himself to challenges, to explore, to wear out hisshoes on the loose slopes, to plunge into the thickets of camel thorn, to search — yet, not to find is the raison-d’étre, so to speak.

It’s funny, after all, that without being fascinated by oneself, the theory of fascination does not work. You cannot fascinate the audience without being fascinatedas an artist. To support this argument, I remembered the “wows” of the viewers, who plunged into a cloud of associations when looking at me.

The climbing artist found enough pseudomalachite near the Shyrgy gorge, but what he desired to find even more were amethysts — a variety of quartz of lilac and red-violet shades. He fell in love with them, so to speak, linearly and “opulently fluttered”22 during his last expedition, when he went to look for the amethysts across the other side of the Dry Pass. For three hours he walked along a gorge formed by a river, whose turbulent stream made its way through the mountain peaks, glaciers, and coniferous forests of Kyrgyzstan. The road was lined with thickets of dense bushes — barberry, mountain ash, sea buckthorn and juniper.

Saturated with the haptic-visual spectacle of the area but never finding amethysts, he decided to turn back to the camp as soon as he suddenly noticed a porcupine. The phenomenon is rare, as these rodents are nocturnal. But this one walked onits short legs in broad daylight along the mountain crevices, slow and waddling. Seeing the artist, it froze but did not run. Its little black eyes sparkled like beads, and its barrel-shaped nose, covered with soft hair, whuffed amusingly.

Suddenly, the porcupine flexed its dorsal muscles and made its quills stand all the way up. It shookits coat, which sounded like a rattle, and then clumsily fled into its underground passage, leaving behind a visiting card, a black and white quill.

The artist came closer and peered into the depths of the animal’s underground passage. And what do you think he saw? On a gray opaque quartz substrate, near the porcupine quill, there were lilac amethyst druses…

CANNOT BUY THE MOONLIGHT

Come closer. Do not be afraid. How strange I must seem to others. People know that I am made of materials commonly used in jewellery craft, which evokes the presence of preciousness. But I am not something that can be worn on the body, though I am assigned a monetary value, as is often done with jewellery. As is the case with my jewellery relatives, people seem to go to great lengths to give themselves the desired appearance to emphasise their physical and social qualities. It is the same with me, a painting made of metal, wood and semiprecious stones. The spectators never cease to penetrate me with their gaze. The same way they study things to buy in their markets.

Semiprecious is another label people have invented to denote the hierarchy of materials and their participation in the market cycle — a word that is commonly applied, for example,to amethyst, onyx or copper. But can a thunderstorm or sun be precious or semiprecious? Do such things have gradations of qualities — or do they just exist?

I have an amethyst in me, and for a while it belonged to the same class as diamonds, rubies, sapphires and emeralds. That is — it and I, too, were considered precious. Until numerous new deposits of amethyst were discovered. But my unique story cannot be discounted.

Not only do I contain a semiprecious stone but that also allows me tobe a vessel for people’s beliefs. Have you ever heard the origin story of my shade of lilac? How Artemis saved the nymph Ametis from the obsessive claims of the god of wine and fun Dionysus? Rejecting the drunken god and fleeing from him, the nymph cried to Artemis for protection and the goddess turned the her into a crystal of purple amethyst, leaving Dionysus with nothing. And so, people believe that when tied to the navel, amethyst neutralises the harmful effects of wine23 and helps prudence prevail. Hence the name amethyst (in ancient Greek: Αμέθυστος, from α– “not” + µέθυστος “to be drunk”).

I also have onyx in me, which is associated with a stream that leads to the mystery of earthly birth — the secret the gods of Olympus bestowed on people. Cupid, having found Venus sleeping on a riverbank, decided to pull the string of his magic bow and make Venus fall in love with him. He missed Venus but hit the tip of her nail with his arrow. A piece of the goddess’s flesh fell into the water of the Indus River and floated to the bottom, where it turned into onyx — a layered and striped mineral meaning literally “nail” in ancient Greek (ὄνυξ). In this story of onyx lies the secret of earthly birth, which materialises through love and with the help of moisture24.

And yet I lack respect for people. They have a strange affection for materials, whether they buy or sell them. I myself am not an animal nor a plant but just a fragment of endless existence — and I am tired of reminding people that they cannot buy moonlight or stars.

Coming from the material world, I still connect a person to something intangible. I am likea channel through which people project their expectations25. For instance, I shape their social presentation by communicating something about theirsocial status or taste to the guests who come to their house. Of course, I sometimes get bored of serving these human constructs. Just as jewellery is tired of servicing thebelief that jewellery is women’s best friend.

Sometimes I want to be seen as fantasy, fictionand sheer inspiration but also to be taken just as seriously by people as capital is. Of course, it’s amusing that people can’t stop thinking that the true meaning of a diamond is formed above their heads rather than below their feet.

THE ROOT OF THE SOUL

Why not get even closer? Can you see the pattern of my wooden blocks? And the steel-framed, polished agates? As piece of art, I am aware of what kind of embodied knowledge is behind these tactile contemplations. Embodied in the sense in which an image on the wall is understood as finalised — having gone through all the steps in the process — finito, so to speak. What was behind the scenes of my finito? What kind of flesh, topographic and situational pulp?

Behind the scenes, there was a workshop with soft and even sweet air. Wood dust gave these qualities to the air. Especially when the room was filled with summer evening light, the particles of wood dust, formed through grinding and then settled on the surrounding objects moved gently as the clothes moved in the room.

Open shelves filled with planks and pieces of wood found by the sea, semi-precious stones in coarse fabric sacks, all creating a sense of organised chaos. Some of the tools came straight from a dentist’s toolkit: diamond and stainless steel drills, tweezers. Some even from that of a surgeon: forceps and clamps. All of this came in handy in artistic endeavours, along with brushes, glues and solvents. Over the years, some of the tools became naturally polished under the grip of the artist’s hand. The streamlined wooden handles of the cutters and chisels were soaked in sweat and took on a greyish brown hue.

How did the wood come into the workshop? Like so — I lie like a tree stump washed on the beach, “breathe mushroom undercurrents”26 in the autumn foliage but I don’t say: “come and take me with you, man walking by,” but his warm hands and open, joyful eyes catch me, and he utters a small purr in surprise. And then I am lifted into the trouser pocket of this artist.

And the elegance of his hands that married the movement of his cutter to my nature will not go unnoticed by the viewer, guiding them to see the world through the eye of the artist and where his breath met the stars. And as I said earlier, he also watched the starts far from North-East of Estonia. He lay in a sleeping bag on the top of a mountain under the vast Issyk-Kul sky, where the bright moon kept him from falling asleep and “the beauty, grandeur, and mystery of the mountains conquered [him] forever”27.

The choreography of the cutter also leads to the white nights and dark days in Estonia. It rains all the time in November and the rest of the seven months are cloudy… colourless. “The colourlessness is a part of the local identity. But it is not intentional, it is about the natural colour of the material.”28 And the materials in me are allnatural. They are not imitations but always genuine. From the natural agate to the glue. Yes, you are not mistaken, not even the gelatine-based glue is artificial. To preparesuch glue, gelatine is taken and dissolved in seven to eight percent vinegar. This glue can be used to glue small stone objects29.

It happens that on white summer nights I lie as agate and feel someone’s eyes on me. The artist twists and twirls me in his hands, turns the lamp off and on to see my advantages and disadvantages under different lighting. Sometimes he even licks me so that the saliva reveals mytexture and lets himimagine what I would look like polished. And then he polishes me, using rotating discs covered with diamond dust. This echoes as a monotonous, rough and metallic sound.

Sometimes the artist also laughs so affectionately while looking at me as if I am tickling him. Am I tactilite30 instead, and not agate after all? Indeed, there wassomething in this artist — he was naively childish, yet calm, warm and balanced31.

His hands seemed to move from the depth, the root of his soul. With geometrically carved joints and the strongest elongated trapezoidal nails, these fingers twisted like branches around hacksaws, chisels, and files, drawing wood dust into the hairiness of his hands, like a tree covered with moss — symbiotically.

Undoubtedly, the tools, sharp as aphorisms, gave his gestures perfection, and the body trusted the dance that had been perfectly learned over the years. However, even without tools, his hands seemed to participate in some kind of choreography. It seemed that the words came to the artist not through the top of his head but through his hand-channels, like roots, greedily absorbing minerals.

The workshop as a space, it turns out, is an extensible concept. It is not only physical and topographic but portable, as it always simultaneously exists in the artist’s head. The workshop is larger than a room. It encompasses pleasure, pain, healing and the constructive channelling of fascination but also many things outside its concrete walls. Captured by the spirit of nature, this artist both saw it and acted — radically, sensitively. This omnifaceted sensitivity was a kind of a resistance — the resistance to rudeness, cruelty, arrogance, excessive seriousness of the world.

As an artwork, I felt all of this — because I was born out of the thickest opaquest flesh of the artist’s worldview, of his body and of his body in the world. As a handcrafted object, I appeal to empathic relation towards the self and remind the viewer that it all started in a cave — in a universal experience for everyone, leading to the collective memory of handicraft32.

In order for a computer algorithm to learn to write in the same way as a living writer, the algorithm needs to experience everything that the writer himself experienced in his life. It is equally difficult for another person to repeat an artist’s handiwork. Therein lies the opacity of experience. I’m not just the tactile sketches by Aleksandr Popolitov. I am the eternal subject of the perception of the world as a whole.

1

Serig, DanielA. 2008. Visual Metaphor and the Contemporary Artist: Ways of Thinking and Making. Saarbrücken: VDM Verlag Dr.Müller, p 13.<https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281032383_Visual_Metaphor_and_the_Contemporary_Artist_Ways_of_Thinking_and_Making> [Accessed 25.12.2020].

2

Huhtamo, Erkki. 2005. Twin-Touch-Test-Redux: Media Archaeological Approach to Art, Interactivity and Tactility. In: Grau,O. (Ed.). 2005. Media Art Histories. Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press.<https://bit.ly/2K7WtLp> [Accessed 08.06.2021], p 5.

3

Gitt, Aala = Гитт, Аала. 2013. Краткое описание развития и жизнедеятельности совсем небольшой компании сподвижников пера и кисти. Апрель. Sillamäe: SillamäeMuseum.

4

Gitt, Aala = Гитт, Аала. 1997. «Апрелю» — пять лет! Силламяэский Вестник, 35(1130).

5

Gitt, Aala = Гитт, Аала. 2003. Творческаябиография. 45 Sillamäe: 10 Aprill. [exhibition brochure]. Sillamäe: SillamäeMuseum.

6

Gitt, Aala = Гитт, Аала. 2013. Краткое описание развития и жизнедеятельности совсем небольшой компании сподвижников пера и кисти. Апрель. Sillamäe: Sillamäe Museum.

7

In the miscellany about the history of the art group April (2013),special attention is paid to theatrical, informal me eting-parties as one of the hinges in the mechanism of the cultural life of Sillamäe. Not directly, but implicitly, these parties influenced the formation of the cohesion of artists, whose practice, in turn, launched enlightenment activities in Sillamäe, including numerous exhibitions at Sillamäe Exhibition Hall. This time of costumed and poetical evenings is briefly described as follows: ‘This miscellany is not for everyone… but for those who lived, ate, drank, chilled while not thinking about wages, jobs and crises in those days… We, the first Aprilists and their confidants longed for Friday. We wrote poems (“stupid”, of course) when dedicating them to each other, gave gifts, were happy for success like children. Those who lived then in a “stagnant” time will understand’.

8

At the so-called “Gluttony Symposium” held on Sputnik (the areawith garden-plots in Sillamäe), participants dressed in various costumes, including ‘certified’ pigs, celebrating the historical transition from collectivism to individualism with all kinds of culinary sophistication.

9

The theme of the 2001 year April exhibition in the Sillamäe Exhibition Hall was body art. A happening was organised, during which not only artists but also visitors were allowed to paint on the human body.

10

At the opening of his solo exhibition in 1996, Aprilist Aleksandr Popolitov, a notable “beard-man” (he wore a beard all his adult life) said: “Dear audience, I would gladly take off my hat in front of you today, but I take off my beard”. And with these words, proceeded to remove the beard that had been gently glued onto his smooth chin with patches by his wife Nadya.

11

Pustovalov, Roman = Пустовалов, Роман. 1997. [Feedback in the guest book].

12

Marina = Марина, surname unknown. 1996. [Feedback in the guest book].

13

Plykin, Borys = Пликин, Борис. 2003. [Feedback in the guest book].

14

D (no continuation of the surname), Karine. 2006. [Feedback in the guest book].

15

16

Unknown authors.1996. [Feedback in the guest book].

17

Popolitov, Aleksandr = Пополитов, Александр.

~ 1984-1990. [Personal diary entries].

18

Popolitov, Aleksandr = Пополитов, Александр.

~ 1984-1990. [Personal diary entries].

19

The most famous waterfall in the Barskoon gorge (Kyrgyzstan); recognised as a natural monument by the state.

20

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 2002 [1945]. Phenomenology of Perception. Translated from French by C. Smith, 1958. London and New York: Routledge Classics, p 26.

21

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 2002 [1945]. Phenomenology of Perception. Translated from French by C. Smith, 1958. London and New York: Routledge Classics, p 26.

22

Kharms, Daniil =Хармс, Даниил. 2005. Малое собрание сочинений. St. Petersburg: Azbuka-Klassika, p 165.

23

Kozminsky, Isidor. 1922. The Magic and Science of Jewels and Stones. New York and London:

G. P. Putnam’s Sons, p 129. <https://archive.org/details/TheMagicAndScienceOfJewelsAndStones/kozminsky-i-magic-1922-RTL014043/page/n313/mode/2up?q=The+amethyst+is+a+species> [Accessed 08.06.2021].

24

Kozminsky, Isidor. 1922. The Magic and Science of Jewels and Stones. New York and London:

G. P. Putnam’s Sons, p 279. <https://archive.org/details/TheMagicAndScienceOfJewelsAndStones/kozminsky-i-magic-1922-RTL014043/page/n313/mode/2up?q=The+amethyst+is+a+species> [Accessed 08.06.2021].

25

Popolitova, Darja. 2020. „Ehe vaatab maailma kultuuri silmadega“, Interviewed by Kaisa Tooming. Häppening.ee.<https://anditshappening.ee/darja-popolitova-ehe-vaatab-maailma-kultuuri-silmadega/> [Accessed 08.06.2021].

26

Tarkovsky, Arseny = Тарковский, Арсений. 2013. Благословенный свет: Cтихотворения. St. Petersburg: Azbuka, p 165.

27

Popolitov, Aleksandr = Пополитов, Александр. ~1984-1990. [Personal diary entries].

28

Elenskaya, Marina. 2013. Twilight Nation. Current Obsession, Spring-Summer (1), p 28.

29

Popolitov, Aleksandr = Пополитов, Александр.

~1984-1990. [Personal diary entries].

30

A fictional name by the author for an archetypal stone for manual artistic processing.

31

Bauer, Sofia = Бауэр, Софья, ~1994, Праздник в государстве под названием «Апрель», [Information about newspaper is missing], [Newspaper scan].

32

Veenre, Tanel. 2015. Handful. Stuttgart: Arnoldsche, p 22.